Learning objectives:

- Understand how dominant views of nature have shaped human - nature relationships

- Learn what intersectionality means and why it matters for biodiversity

- Recognise who is most affected by biodiversity loss and why

Humans and Nature: philosophical foundations to our relationship with nature

Reflection (3’)

Prompt: Take a piece of paper and draw nature and biodiversity, and humans. Where do you position humans in relation to nature and biodiversity?

In many modern societies, nature is commonly viewed as separate from humanity: an external resource to be studied, controlled and used for human benefit through science and technology.

This worldview has deep roots in European intellectual history. Prior to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, many in Europe understood the world as a living, divinely ordered, and interconnected whole in which humans had a meaningful place. But from the 16th century, this perspective began to shift.

Thinkers like René Descartes and Francis Bacon helped lay the foundations of modern science.

Descartes argued that humans, as rational minds (‘I think, therefore I am’ - Discourse on Method, 1637), were fundamentally distinct from the material world, which included our bodies and the rest of nature. This view is referred to as ‘Cartesian dualism’ and contributed to seeing nature as passive, like a machine. Descartes wrote that humanity could become ‘masters and possessors of nature’ (Discourse on Method, 1637) through reason.

Bacon promoted the idea that science should aim to uncover nature’s secrets and put them to use for human progress.

These ideas shaped a mechanistic and extractive mindset, in which nature was no longer something humans belonged to, but rather a system to be measured, manipulated, and exploited.

This philosophical shift helped establish the foundations of modern industrial society and the exploitative relationship with the environment that dominates many contemporary Western systems.

Intersectionality and biodiversity loss

As we have seen, European ideas relating to nature and our domination over it have a long history. The world we inhabit today has been shaped by these dominant ideas that relate to nature.

Parts of your identity such as your race, gender, class and ability can influence your access to the benefits that nature provides, and give you more or less of a say in decision-making about the natural world. So, who people are, and what constitutes their identities, becomes important when considering how people have different experiences of, and access to, nature.

We all hold multiple identities simultaneously. These identities don't just sit side by side: they intersect and interact to shape unique lived experiences of privilege or oppression. This dynamic interplay is what we call intersectionality.

The term intersectionality was coined by American civil rights advocate and scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s (Crenshaw, 1989).

Crenshaw introduced the term to describe how people who sit at the intersection of multiple marginalised identities, such as Black women, often fall through the cracks of legal and social protections. Crenshaw recounts the case (1976) of Emma DeGraffenreid, a black woman who, alongside other black women, had sued General Motors for discrimination. Their claim was that General Motors did not hire them because of their race and gender. The court dismissed their case because the company had both Black employees and women employees, ignoring the unique discrimination faced by Black women as a group. The issue raised by Emma was that the company had hired black employees for industrial work, who were men, and women for secretarial roles, who were white. Her experience was not simply about race or gender, but the intersection of both. The existing legislation was not nuanced enough to give her adequate protection (Crenshaw, 1989).

Just as people can experience overlapping forms of discrimination, so too do communities experience overlapping environmental (in)justice, including being disproportionately affected by biodiversity loss, or having less access to nature.

Those most affected tend to be (a combination of) Indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, women, low-income populations, and particularly (but not only) in the Global South. These groups contribute the least to ecological degradation yet bear the brunt of its consequences.

This unequal impact is often reinforced by the delegitimisation of non-Western knowledge systems. Modern Western worldviews and scientific approaches frequently dismiss Indigenous and local understandings of nature as unscientific or inferior. Under this logic, groups seen as lacking ‘proper’ knowledge are excluded from biodiversity governance and decision-making. This marginalisation is used to justify their displacement, despite the fact that their cultural, spiritual, and material survival is intimately tied to the ecosystems they protect (IPBES, 2025).

Indigenous Peoples and local communities are not only rightful stewards of their lands, but they are also more successful at maintaining ecological integrity. For example, because they derive their means of subsistence and meaning directly from their relationship with the immediate environment, Indigenous Peoples have a direct interest in the protection and restoration of the ecosystems that their livelihoods depend on. They also have in-depth knowledge of the land acquired and transmitted across generations, and ways of living which are often more conducive to a harmonious relationship with nature.

Adopting an intersectional approach means recognising and challenging all the power systems that result in specific experiences of exclusion or oppression. It involves amplifying marginalised voices, challenging systems that silence or exclude, and valuing diverse ways of knowing and being in relationship with nature. Ultimately, an intersectional lens allows us to move toward biodiversity solutions that are more just, inclusive, and effective.

Case study: Education for resistance in the Amazon

Watch: Outdoor Class in the Amazon – Indigenous Citizenship

Let yourself be inspired by this teacher from the Federal University of Western Pará who took students on an ‘outdoor class’ to a protest led by Indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon. The protest opposed legislation threatening Indigenous peoples’ rights to in-person education in the state of Pará. Through direct involvement, students linked education with political action for environmental justice to safeguard the rainforest and Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Case studies: Injustice and the biodiversity crisis

The biodiversity crisis is unjust in many ways: not just for non-human life, but also for people, especially those already experiencing poverty or exclusion.

In many countries around the world, and particularly in the Global North, economic growth is the main goal of the dominant socio-economic system. Because the growth-oriented economic system leads to overproduction and overconsumption, it comes with extracting more and more from nature. This is how economic growth contributes to biodiversity loss (Otero, et al., 2020), as well as other environmental issues, such as climate change.

The resulting wealth is very unequally distributed among countries, and within countries (Khalfan, et al., 2023).

This means that when our economic system systematically prioritises economic growth over ecological integrity and people’s wellbeing, it undermines the wellbeing of all forms of life, to the profit of a few wealthy and powerful countries, companies and individuals.

As in the context of the climate crisis, the Global North reaps the most benefits from a growth-oriented economic system whilst the Global South suffers the worst of the consequences of biodiversity loss, especially those areas with Indigenous peoples and high levels of poverty.

These communities have less power, less political voice, and depend directly on nature, so they are affected more, even though they contributed little or nothing to its destruction.

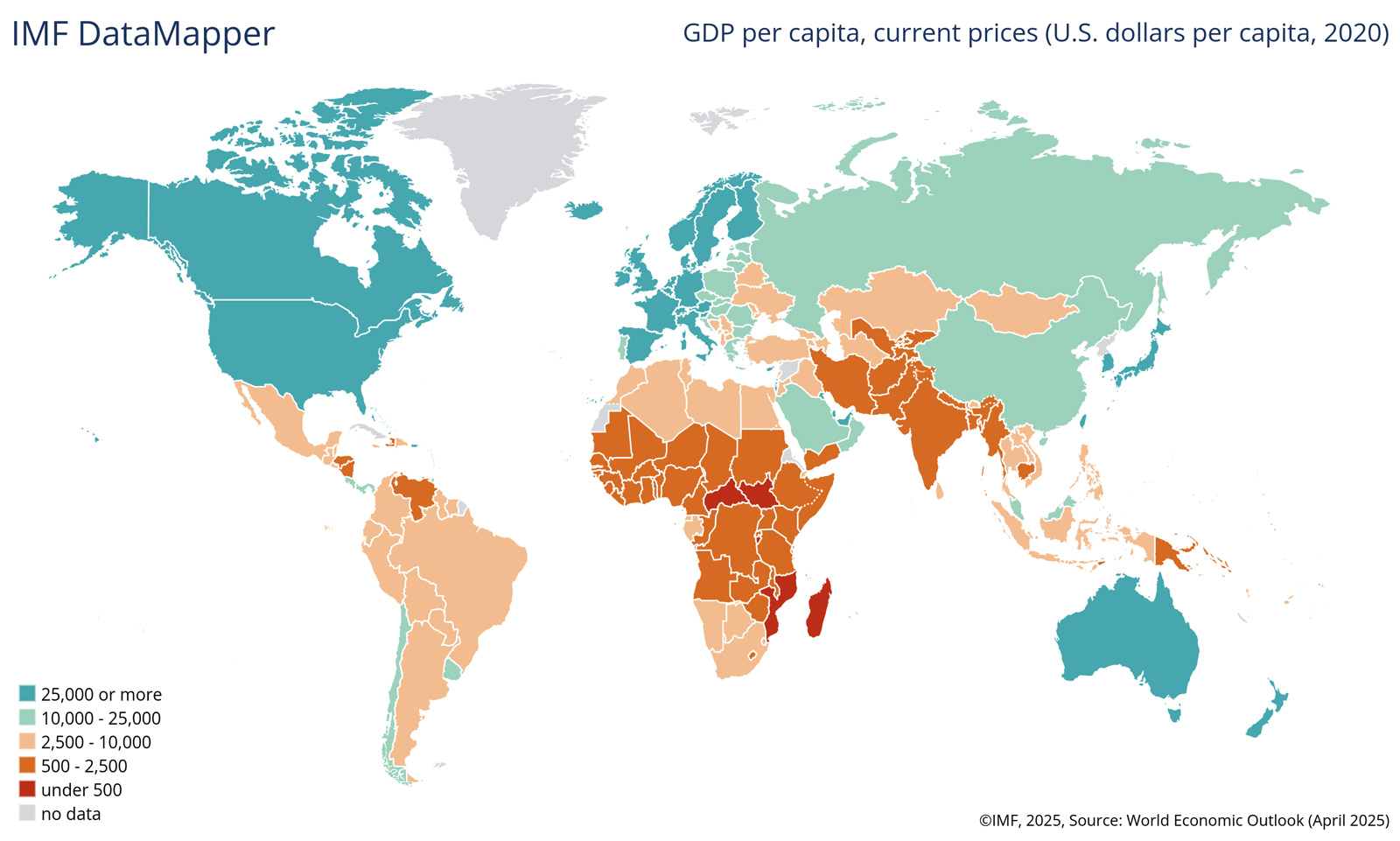

These inequalities can be visualised by comparing two global maps:

- Figure 1: Biodiversity Intactness Index, showing loss of biodiversity (already shown in section 2.1)

- Figure 2: Global distribution of GDP per capita, a proxy for economic wealth

Areas with high biodiversity loss (light regions in Figure 1) often overlap with those that derive little economic benefit from the current global economy (orange/red in Figure 2). These regions face local losses of ecosystem services vital to millions of people, for example, in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Even within countries, inequalities persist.

Take the Niger river delta in Nigeria: a wetland ecosystem that provides an estimated $25 billion in provisioning services and is vital for local communities. In contrast, local oil production, despite generating three times less economic value, is prioritised, with profits funnelled to distant shareholders. Meanwhile, the ecological destruction caused by oil operations is borne by the local communities who depend on the wetland for food, water, materials, and medicine (Adekola, et al., 2015). It is estimated that 31 million people live in the Niger river delta (Acey, 2016).

Reflection (5’)

Prompt: Where do your social identities place you in relation to biodiversity impacts? Reflect on how your background, privileges, and vulnerabilities including your age, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, income, class, level of education, where you live, etc. shape your relationship with biodiversity and nature, both in terms of exposure to its loss and your role in protecting it.