Learning objectives:

- Understand what human activities are causing biodiversity loss

- Learn how current views, economic and political systems contribute to the biodiversity crisis

- Explore why action to protect biodiversity is often blocked

Direct drivers of the biodiversity crisis: human activities

The primary drivers of biodiversity loss are the direct impacts of human activity on ecosystems. Industries such as agriculture, construction, mining, fishing, and forestry are placing unprecedented strain on the natural systems that sustain life.

These pressures have caused species extinction rates to rise to levels 10-100 times higher than average rates over the last 10 million years (WHO, 2025).

IPBES identifies five key mechanisms through which human activities directly harm biodiversity: land and sea use change, direct exploitation, climate change, pollution and invasive species (IPBES, 2019).

Land and sea use change

The conversion of natural landscapes for agriculture, urban development, or industry has significantly disrupted habitats (IPBES, 2019):

- 75% of Earth’s land surface has been altered by human activity.

- 66% of the oceans have been significantly affected by human use.

- 85% of wetlands (some of the planet’s most productive ecosystems) have been lost.

These changes continue to accelerate.

Exploitation

Human extraction of natural resources, through harvesting, hunting, logging and fishing, has led to significant species declines. In marine ecosystems, overfishing is the single largest driver of biodiversity loss.

Climate change

Greenhouse gas emissions are changing global climate patterns and consequently, degrading habitats. As ecosystems become unliveable, species must adapt, migrate, or face extinction. Many cannot respond quickly enough to survive.

Pollution

Pollutants, such as plastics, heavy metals and nitrogen runoff, enter ecosystems through human activity. These substances harm both individual organisms and ecosystem functioning.

Invasive species

Increased human movement and trade have led to the widespread introduction of non-native species into ecosystems. These invasive species often outcompete native ones and destabilise ecosystems, especially those already weakened by biodiversity loss.

As ecosystems lose biodiversity, they become more vulnerable to further disruptions, leading to non-linear, accelerating impacts.

One outcome of this fragility is the potential for trophic cascades. These are chain reactions within ecosystems where changes in the population of one species lead to dramatic shifts throughout the entire system.

What is blocking meaningful action on biodiversity?

Despite growing scientific consensus and public awareness, global pressures on biodiversity continue to intensify (IPBES, 2025).

IPBES identifies not only the direct drivers of biodiversity loss, but also the underlying, indirect barriers that prevent meaningful change.

These challenges can be understood across three interconnected levels (IPBES, 2025):

- Views: dominant beliefs and values

- Practices: the ways we live, consume, and govern

- Structures: how societies and economies are organised

To truly address the biodiversity crisis, we must transform these foundational layers (IPBES, 2025).

Below are three deeply rooted systemic causes to why change in support of biodiversity has been so difficult to achieve (IPBES, 2025):

1. A worldview of separation and domination

Modern societies view nature, and certain groups of people, as resources to be controlled or exploited.

This perspective was prevalent during colonialism and persists in systems that value people or ecosystems only to the extent that they serve dominant interests.

This worldview:

- Enables the exploitation of labour, knowledge, and ecosystems

- Delegitimises alternative knowledge systems (e.g. Indigenous worldviews) that promote relational and sustainable ways of living

2. Concentration of wealth and power

Certain individuals and institutions control most of the global wealth and decision-making. These actors can resist transformations that threaten their interests, including policies aimed at protecting biodiversity.

- Low-income countries, rich in natural resources, are often trapped in exploitative global systems.

- Inequities in international finance and trade prevent many countries from adopting ecologically sound alternatives.

- These same countries are often those most vulnerable to biodiversity loss.

3. Short-termism and consumerism

The dominant economic model prioritises short-term, individual material gain over long-term wellbeing and planetary health.

- The prioritisation of economic growth drives unsustainable levels of production and consumption.

- Environmental costs are often hidden from consumers through geographic and economic distance from production sites.

- These patterns are reinforced by social norms and habits, making unsustainable living appear normal and necessary.

It is therefore crucial to learn about biodiversity and the drivers of biodiversity loss, to interrogate our own views and impact on nature and other people, to expose and challenge dynamics of power and inequality, to make visible the bonds between all forms of life, and to promote the prioritisation of wellbeing for all, including for nature.

Through your educational work, you have a key role to play in this shift. You can guide and encourage students to see the bigger picture, to question systems that harm both people and the planet and to imagine how we could do things differently.

You can also help students develop values of sustainability, wellbeing, and equity, as well as deepen their connection with nature. You can do so by teaching about nature’s importance and beauty, and by organising outdoor activities such as the Nature Hike or the Mindfulness activities that bring students to experience and immerse themselves in the living world.

This reflects an insight long held in Indigenous and peasant communities, but often forgotten in Western societies: we are all interconnected - humans, animals, plants, and the ecosystems we share. And because of this interconnection, we carry a responsibility to care for one another and for all forms of life on Earth.

Does nature have value beyond serving humans?

Framing nature in terms of ecosystem services helps illustrate how all aspects of human life depend on biodiversity. As IPBES notes, the functions supported by biodiversity are often irreplaceable (IPBES, 2019). Without them, human life and wellbeing would not be possible.

Yet, unchecked human activity, driven largely by the profit interests of wealthy and powerful countries, companies and individuals, continues to degrade ecosystems.

In high-income countries, many people are shielded from the ecological cost of their consumption, which is often outsourced to vulnerable ecosystems and communities.

Reflection (5’)

Prompt: Watch this clip from the Ocean (2025) documentary narrated by Sir David Attenborough, showing the destructive impact of bottom trawling on marine life. This is the hidden ecological price behind cheap fish.

After watching, journal your responses:

- How did these scenes make you feel?

- How do you feel toward the fish depicted in the clip?

How is it that humans are so dependent on and connected to nature, yet often behave as if separate from it?

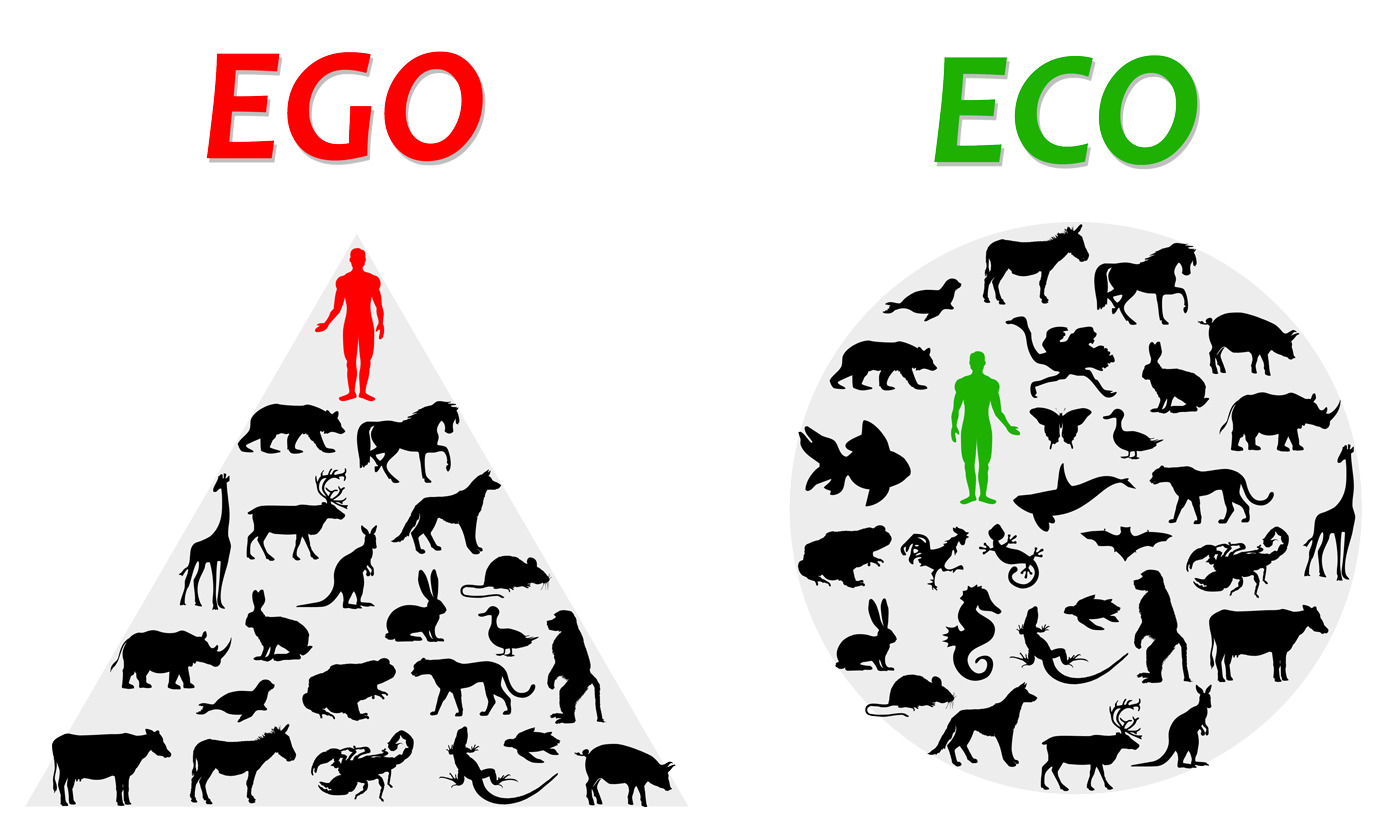

This contradiction is rooted in anthropocentrism: a worldview that places human beings at the top of the pyramid. From this perspective, nature has value only insofar as it serves human needs (Encyclopaedia Britannica, n.d.).

Anthropocentrism is present in much of Western philosophy (such as Cartesian dualism), religion, science, economics, politics, culture. It portrays humans as rational and superior, while nature is framed as chaotic, and subject to human control.

This anthropocentric worldview underpins a mindset in which nature is seen as a ‘free’ bundle of resources to be used and discarded.

But many Indigenous cultures embrace fundamentally different worldviews. In these relational philosophies, humans are part of a vast, interconnected web of life, alongside animals, plants, fungi, rivers, and even geological features like rivers or rocks.

These systems often reflect biocentric (all life has value) or ecocentric (all nature, living and non-living, is inherently valuable) perspectives. Many believe we should learn from Indigenous cultures, which have had balanced relationships with nature for millennia, to inform how to address the current climate and biodiversity crises.

How we see our place in the world - either separate from and above nature, or as part of it - shapes how we value biodiversity, and how we act toward it.

Reflection (10’)

Prompt: After watching this 5-minute video on anthropocentrism, journal your thoughts:

- What feelings or questions did it provoke?

- Did it challenge your usual thinking about nature and humans?

- Should Indigenous worldviews have more influence in environmental decisions?

- Can you see links between anthropocentrism and today’s economy?

Anthropocentrism has also shaped the dominant socio-economic system, with economic growth measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as its main goal.

GDP adds up the value of all the goods and services produced in a country, over a period of time, typically one year.

But GDP is limited: GDP doesn’t measure who benefits from economic growth. It doesn’t count inequality. It doesn’t count pollution or greenhouse gas emissions. It doesn’t subtract the destruction of forests, or the extinction of species. GDP even rises after oil spills, because cleaning them creates economic activity (Maigné, 2025).

The current economic system often ignores nature. But the reality is that the economy is embedded within the biosphere and the physical world (Mayumi, 2017). The economy cannot grow indefinitely on a finite planet.

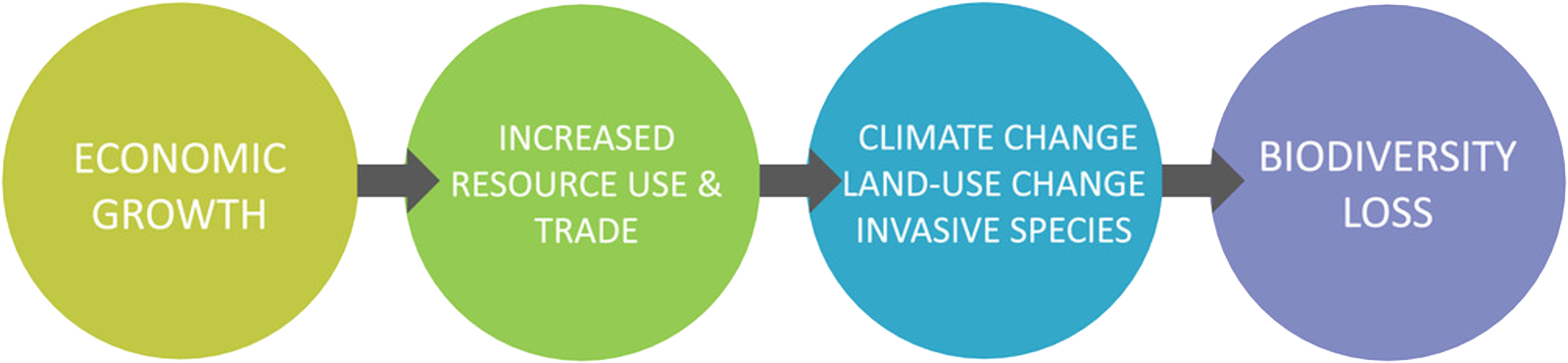

Increasing evidence shows that economic growth leads to greater use of resources and trade, which contribute to higher greenhouse gas emissions, land use change and invasive species. These, in turn, lead to biodiversity loss (Otero, et al., 2020).

Between 1992 and 2014, global GDP per capita rose by over 60%, while natural capital (including biodiversity) declined by nearly 40% (OECD, 2021).

In other words, the human activities that drive biodiversity loss are accelerated by a growth-oriented economic system. Loss of biodiversity is not a glitch; it is the consequence of an economic system that comes with unsustainable levels of production and consumption.