Overview

Pathbreak: Biodiversity JENGA® uses JENGA® bricks with a customised gameboard (see below in Figure 1) to illustrate in an engaging way how biodiversity loss can lead to ecosystem collapse, and further spark conversations about biodiversity loss.

Learning objectives

This game shows how removing species from an ecosystem through harmful human practices can destabilise the ecosystem. However, it also shows that we can help species come back, through restoration or other environmentally friendly activities, thereby bringing back some stability to the ecosystem.

Play has long been essential to how humans learn and grow, and its importance in education continues to increase. Games can transform learning from a passive experience into an active and engaging one. When thoughtfully integrated into the classroom, games offer powerful opportunities to develop skills, improve memory, and spark creativity, often more effectively than conventional teaching methods (Robert, 2024).

Links with the other resources and duration

This game can be played as an ice breaker, or as part of any lesson or activity that is linked to biodiversity or ecosystems.

In the context of the PLANET4B educational materials, this game is played during Lesson 1 of Biodiversity and the natural world in crisis for secondary education, and before Lesson 1 of the same module for higher education.

The game can take anywhere from 15’ to 1 hour, depending on how much time you can allocate to the Debriefing phase at the end.

Introduction

Ecosystem collapse

An ecosystem consists of all the living beings in an area and the way they affect each other and the environment. Ecosystems often include humans, as we directly influence the environment around us.

Within an ecosystem, each organism plays a role, and many depend on each other to survive. For example, bees pollinate plants, which then grow fruit and feed birds, while birds also eat insects and control insect populations, protecting trees and fruits, while fungi break down waste, turning waste into food for plants. Everything in an ecosystem is connected in one way or another, and these connections and dependency between different species give a natural balance to the ecosystem.

But what happens when some species disappear? The balance begins to break down. Often, multiple species have the same role. However, today the rate of species loss is much higher than many ecosystems can bear. According to WWF, the rate of species loss is 1000 to 10 000 times higher than natural extinction rates. This means that ecosystems don’t have time to adapt to this rapid loss of its parts.

Not all species contribute to ecosystem stability equally. There are so-called ‘keystone species’ whose loss can have many cascading effects on ecosystems.

The wolf is a keystone species because no other animal can replace its function of controlling the herbivore population. If wolves become extinct from a certain area, or their population drastically reduces, the number of herbivores, such as deer, drastically increases, because they are not being eaten by wolves. Too many deer eat too many plants and young trees - a problem called overgrazing. This harms other animals that depend on the plants, and can even change the landscape, soil, and rivers over time.

Show students this four-minute video on how wolves change rivers.

Pathbreak: Biodiversity JENGA®

In Pathbreak: Biodiversity JENGA®, the idea is that the wooden blocks represent species. The tower is an ecosystem composed of different species. Players use a customised board (Figure 1) and die. The player uses a die to move a token around the board, following the instructions on the square they land on. The squares on the board will require the player to remove or add a block or blocks of a particular type, such as a bird or an insect, and indicates why this block/ species is being removed or added.

For example: there are too many pesticides, so you have to remove an insect; or, there have been hedgerows planted in an agricultural area, and now birds are coming back, so add a block. The game finishes when the tower collapses - signifying ecosystem collapse.

Materials

This game should ideally be played with up to 6 players. If you have a large class, you can either prepare for as many groups as your class needs, or divide students into several teams, where students rotate when it’s their team’s turn.

- PDF printout of the gameboard in colour (you can also laminate it to reduce damage if the game is going to be played a lot)

- Die

- Tokens to move around the board, one per player (this can also be a coin or a similar object, or you can cut out the tokens that are printed next to the gameboard)

- A JENGA® game with the ends of the bricks coloured to correspond with the different species colours on the gameboard, as explained below

Pre-game preparation

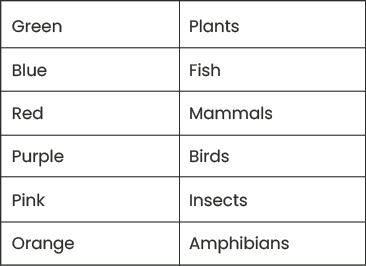

Ahead of the lesson, you should colour the ends of the bricks according to the six colours on the board. See table below for colour allocation:

In a typical JENGA® set of 54 bricks, there will be nine bricks of each colour.

To colour the bricks, you can use pens, paint, nail varnish, crayons, coloured stickers, etc., but make sure you only add colour to the ends as the other surfaces of the bricks are designed to slide against each other.

Detailed game instructions

Assemble the tower in the middle of the board in alternating layers of three bricks.

Roll the die to determine who goes first.

Players can start from any corner of the board.

The first player rolls the die and moves their token to the corresponding number of spaces in a clockwise direction.

The player follows the instructions on the square.

For example: Forest fire, remove one plant.

As the facilitator, you can narrate the game and say: A forest fire occurred, and the woods are burning. With climate change and temperature rising, forest fires are happening more often across the world. A forest fire means we are losing plants. Plants are marked by the green colour, so remove any wooden brick that is coloured green.

The player then removes a green brick from the tower and places it on top of the tower.

There may be more than one instruction on the square. In this case, both instructions should be followed.

When bricks are removed, this cannot be from the top layer of the tower unless the instruction is ‘+1’ species. In this case, the player may take that species (if it is available) from the top of the tower and position it in a space lower down the tower where a brick has already been removed. This may stabilise the tower, or it may not!

If the board indicates that a colour should be added that is not available in the top layer of the tower, the game passes on to the next player.

If the tower collapses when a brick is being added, this can be an example of restoration gone wrong. It is very difficult for us to understand the complexity of ecosystems with so many species interacting in multiple ways. Sometimes it is difficult to predict how an ecosystem will react, even if we are trying our best to help it thrive.

Continue playing until the tower topples - the ecosystem has collapsed!

You can use the game as a short icebreaker for a lesson, recognising the limitations of the game to mimic a real ecosystem: the tower is built randomly, but with ecological theory, the ecosystem has plants and insects at the bottom of the food chain, and apex predators at the top, and there are feedback loops within the system (e.g. if the tower were built with the apex predators at the top and we took one off, it would have no effect, but in reality the removal of apex predators would have a significant impact on the whole ecosystem). There are no reptiles in the game, and for the six classes/genera the number is equal for each, whereas ecosystems largely contain more plants and insects, than birds or mammals. The primary focus of this activity is awareness of the real risks of biodiversity loss and starting the conversation.

You may choose to ask some questions to build understanding, such as, but not limited to:

- Could you predict when the ecosystem was going to collapse?

- Which actions on the board are directly related to climate change?

- Is there anything you might do differently as a result of playing this game?

- What are the limitations of this model compared to a real ecosystem?

Debrief

Debriefing is a collective discussion method that can help students process and make sense of their thoughts and emotions and identify next steps for action in a safe space, following creative methods and interactive lessons.

As you know your students best, you can carefully think of questions, choose from the selection below or adapt the questions proposed according to the age and knowledge of your students.

You can also look at the instructions in the separate Debriefing activity to help you organise the debrief.

If you have a large group, or you know that some shy students would not want to answer in front of everyone, you can ask students to write down answers to your questions.

Here are some questions we recommend as a debrief from this game:

Emotional reflection

- How did it feel when you had to remove a block from the tower?

- Were you nervous at any point in the game? Why?

- What emotions did you experience when the tower collapsed?

- Did you feel responsible for the tower falling? Why or why not?

- Did any moments in the game surprise you or make you think differently?

Synthesising learning

- What did the tower represent in our game? What did each block represent?

- How did your actions affect the stability of the ecosystem (the tower)?

- What does this game teach us about how nature works in real life?

- Can you think of real examples where removing just a few species caused bigger problems?

- Were there any points in the game where you saw the system become weaker or stronger?

Generating ideas and taking action

- What are some human actions that cause species to disappear in real life?

- Can you think of things people or communities can do to protect biodiversity?

- What role do you think you can play in helping ecosystems stay balanced?

- What new questions do you have about biodiversity after playing the game?

- Did this game give you any ideas for a project, artwork, or story about nature?