.png)

Please note that some of the activities in this online course require watching a video in English. You can select subtitles in your own language, if they are available. If they are not available, you can select auto-translation of subtitles into your language from each video’s settings on YouTube.

Learning objectives:

- Understand how natural systems improve people’s quality of life

- Reflect on how the more we personally value nature, the more we benefit from it

- Understand how more biodiverse nature gives us a greater sense of wellbeing through connecting with it

Nature’s contributions to people

The Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) describes, in its 2019 Global Assessment Report, the overwhelming benefits that nature brings to people (Brauman, et al., 2020). Natural systems underpin vital functions that ultimately influence our quality of life.

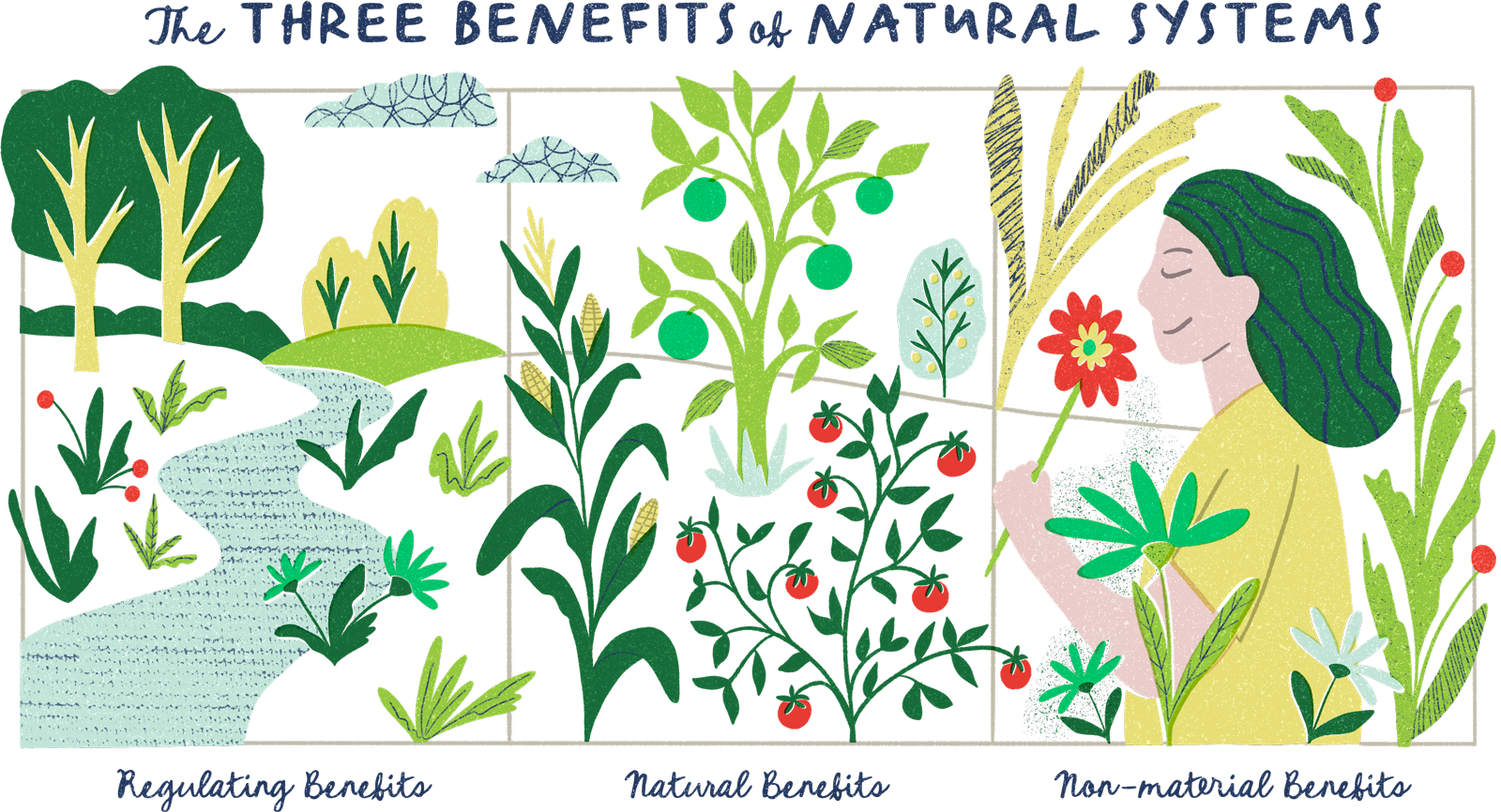

Natural systems provide:

- Regulating benefits such as regulating air quality or water quality, which in turn help to reduce things like disease or water treatment costs.

- Material benefits such as food and food quality, helping to reduce hunger and malnutrition.

- Non-material benefits such as contributing to people’s sense of identity or spirituality, improving things like mental health, cultural identity and life satisfaction.

The extent to which society benefits from nature’s contributions depends on the extent to which human activity is impacting these natural systems. The more natural systems are impacted by human activities, the more we lose the regulating, material and non-material benefits that nature provides.

At an individual level, through conscious and deliberate efforts, it is possible to increase the benefits you receive from nature by taking time to better understand, interact and connect with it.

Yet, it is essential to recognise that not everyone experiences equal access to nature. Some individuals can experience various barriers to access and connect with nature based on their ability, age, class, ethnicity, gender, income, migrant status, race, religion, etc., or a combination of these.

Remember the concept of intersectionality that was discussed in the Biodiversity and the natural world in crisis module? Here, intersectionality helps us understand how overlapping identities, including those mentioned above, shape people's access to nature and their enjoyment of nature’s benefits.

‘Green spaces are white spaces’ said one of the members of the PLANET4B case study Opening Nature to Black, Asian and ethnic minority communities. She was referring to not always feeling welcome in countryside spaces because of rural racism. Community-led organisations, such as Dadima’s CIC walking group, help minoritised people gain confidence in nature through supportive relationships and education. For example, many of the walks include guest speakers or community members sharing insights on various aspects of nature. Through a series of workshops, members of a Learning Community made up of Dadima’s walkers explored and found their voice in the biodiversity conversation. Watch the short film below exploring why people from diverse cultural backgrounds may find it difficult to access natural spaces, how Dadima’s Community Walks are breaking down these barriers, and how important community is in bringing everyone closer to nature. Let yourself be inspired by the benefits that people experience through spending more time together and in nature.

In Oslo, Norway’s most biodiverse urban region, children and youth with disabilities often face exclusion from organised outdoor recreation. In an expert meeting organised within PLANET4B’s case study, individuals with lived experience of disability were given an opportunity to share their stories of sleeping in a hammock in the forest with adaptive gear, and building an igloo, with the leader of the Greater Oslo Recreation Council. Rather than focusing on limitations, they emphasised possibilities. This shift in narrative, from barriers to potential, was pivotal, and the Recreation Council has gone on to initiate new collaborations with disability organisations, contributed feedback to municipal mapping of outdoor areas, and begun embedding inclusive design into its strategic planning.

Graz, Austria boasts 30 community gardens, however, migrant women, single mothers, and elderly women living alone often face barriers – physical, linguistic, and symbolic – that can prevent them from participating. PLANET4B’s case study here established a new community garden. Over time the women that participated grew in confidence, ‘Before, I thought this kind of thing was for other people. Now I know it can be ours.’ The GAIA Gartenberg is now more than a garden. It is a nucleus for an emerging community park, with a second garden and orchard meadow already underway. The municipal green space department has become a committed partner, and lessons learnt from the case study are feeding into Graz’s urban development strategy.

In Erfurt, Germany, another PLANET4B case study sought to engage migrants around the topic of biodiversity. Young people can feel disconnected from nature and excluded from environmental decision-making. Migrants, newcomers, and those from international communities are particularly affected, compounded by structural barriers such as language, migration status, and experiences of discrimination, particularly where far-right politics are more prominent. The case study created a space where young people could feel safe, seen, and heard. Through participatory workshops, nature-based retreats, and creative interventions, biodiversity became a shared language. Outdoor cinema, experiential games, and hikes helped youth move from passive concern to active engagement. As the weeks passed, roles began to blur - facilitators became learners, youth became leaders – showing what is possible when young people are given the opportunity to lead.

Encouraging connection with nature must therefore involve addressing such barriers to access to nature. In this module, we’ll explore some of the many benefits of connecting with nature, in the hope we can encourage both educators, and through them, students to spend more time in nature, while also encouraging educators to consider how to make these experiences more accessible and meaningful for all students.

The extent of the wellbeing we receive from nature depends on how much we value nature

Reflection (3’)

Prompt: How much time do you spend in biodiverse, natural spaces every week and how does this make you feel? When you go to such spaces, do you do so with the purpose of spending time in nature or are you just passing through to go elsewhere?

The aim of the above exercise is to reflect on how much time we spend in nature in our day-to-day lives and whether we do so with the purpose of connecting with nature or not.

Spending time in natural spaces and connecting with nature offers a multitude of psychological, cultural, spiritual and physical benefits. This includes feelings of relaxation, recreation and the aesthetic appreciation of the beauty of the natural world. These benefits are what we refer to when we say that being in nature improves our wellbeing.

Increasingly, new research demonstrates the many ways in which spending time in nature, connecting with, and valuing nature, can benefit people (Frumkin, et al., 2017). Often this research articulates in a scientific language something which may already seem obvious to many people. However, it can be helpful to have a clear evidence-base to make the argument to those who may not feel very connected to nature, or to advocate for better decision-making around making natural spaces accessible to everyone, not just a privileged few.

For example, research has shown that increased time in nature and outdoors has been found to improve self-esteem, depression, anxiety, happiness levels, immunity, sleep, cardiovascular disease, and lower blood pressure. It has been found that children and teenagers who spend time in nature have better mental health, including reduced stress levels and a higher quality of life (Tillmann, et al., 2018).

Spending time in nature can also increase the sense of self-transcendence, which is the feeling of belonging to something greater (Castelo, White, & Goode, 2021). Self-transcendence can help people deal with grief and suffering (Ge & Yang, 2023).

However, in keeping with the above findings, research has also shown that the amount of benefits a person will receive from spending time in nature depends on the strength of that person’s connection to nature (Chang, et al., 2024). A person with a stronger connection to nature enjoys more wellbeing benefits from it - such as a reduction in stress, anxiety and depression - than a person who doesn’t have a very strong connection with nature (Bratman, et al., 2019).

In short, the extent to which spending time in natural environments improves your wellbeing depends on how much you value nature.

This finding underscores the importance of fostering strong environmental education in young people - especially those who do not have easy access to green spaces - to encourage a greater sense of connection with and value for nature. As you may have already experienced yourself within your teaching practice, one of the best ways to do this is to take young people out of the classroom and into natural environments. Experiential learning in green spaces is an excellent way to cultivate a personal sense of importance for the natural world.

More biodiverse nature brings us more wellbeing

Recent research has shown that not only does exposure to natural environments improve our wellbeing but that, the more biodiverse those environments are, the more we stand to benefit from them (Hammoud, et al., 2024).

In order to determine the causal link between how more biodiverse nature brings us more wellbeing, researchers used real-time data from over 41 000 assessments collected globally over a 5-year period by 2000 participants who used a smartphone app to report on their findings (Hammoud, et al., 2024). The study produced fascinating results, including:

- Hearing or seeing specific natural elements such as birds, trees, plants, water was associated with increased mental wellbeing.

- Environments with a greater variety of natural features (or natural diversity) had incrementally stronger positive effects on mental wellbeing than less naturally diverse ones.

- The benefits of natural elements, especially from birds, trees and plants, persisted for up to 8 hours after exposure.

This study underlines the importance of not just ensuring that people are able to have access to nature (particularly in urban areas) but that the biodiversity of the natural environment matters too.

In short, it is not just the presence of natural features that can improve our wellbeing but also the richness and the variety of the nature that we are exposed to.

Differences in access to nature

Access to nature and naturally rich environments is something that is unevenly distributed across different groups of people. Not everyone has equal access to green spaces.

In cities, socially vulnerable or disadvantaged social groups often have less access to biodiverse environments, leading to inequalities in access to associated health benefits (European Environment Agency, 2022). This is because poorer neighbourhoods tend to have less green space than richer ones and thus children who grow up in lower socio-economic neighbourhoods will have less access to urban green spaces.

Tragically, this inequality is compounded as children from low socio-economic backgrounds not only have less access to the benefits of nature, they also have less access to outdoor play and more exposure to environmental risks such as air pollution, bearing consequential health impacts (Rehling, et al., 2021).

As we have seen in the above section, people who receive the most benefits from their time in nature are those who value nature and their connection to it. If children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds have less equal access to nature, this suggests that they may likely have fewer opportunities to form a strong connection to the natural world from an early age.

As an educator, regularly exposing young people, especially those from less advantaged backgrounds, to biodiverse, natural spaces will help them foster lasting, meaningful connections with nature. These early experiences can lead to improved lifelong health and wellbeing through helping young people bond to and value nature, which in turn may also motivate them to take action to protect and restore biodiversity.

Unequal distribution of environmental burdens: Environmental injustice

As explored above, not only do people from different backgrounds have unequal access to nature, but marginalised communities have higher exposure to environmental risks, such as air pollution.

This unequal distribution of environmental risks placed on low-income communities, communities of colour and Indigenous peoples is observable around the world and is called ‘environmental injustice’ (Institute for Environmental Research and Education, 2025).

Environmental justice is a social justice movement, as well as a research field. It emerged from the Civil Rights Movement in the second half of the 20th century. Communities of colour and communities living in low-income neighbourhoods began to point out that they were disproportionately exposed to toxic waste, landfills, polluting industries, and poor environmental protections.

As research around this issue developed, it became clear that environmental issues are not distributed randomly, but tied to racism, economic inequality and power imbalances. This shifted the view of pollution from a purely ecological to also a human rights issue, recognising that environmental problems are deeply social and political (Bullard, 1990).

Today, the environmental justice movement has spread to observe global differences. So-called ‘less developed’, poorer countries often bear the environmental costs of production of products consumed in wealthier nations, from pollution caused by mining to that of factories. Impacted communities are often excluded from decision-making spaces and lack access to legal representation.

Across scales, a pattern emerges - if you are marginalised, based on your social, economic or racial and ethnic background, or a combination of these, you are likely to have less access to nature and greater exposure to pollution, resulting in significant health consequences.

These patterns indicate that environmental harms are not simply the result of local problems, but of deep structural inequalities embedded in economic and political systems. Environmental injustice is a symptom and consequence of broader inequalities, such as poverty and racism (Institute for Environmental Research and Education, 2025).

The Environmental Justice Atlas is an open-access online resource that maps and documents environmental conflicts around the world. It was created in 2012 and is moderated by researchers at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, working with activists and community organisations. The Atlas currently contains over 4,000 cases of conflicts linked to mining, dams, waste, energy production, industrial agriculture, deforestation, urban development, and more. Each entry provides: a short summary of the conflict and its history, who are the actors involved (communities, companies, governments, NGOs), the environmental, social, and health impacts, the forms of resistance and mobilisation used by local people and the outcomes (successes, setbacks, ongoing struggles).

The Environmental Justice Atlas can be used as a powerful tool in education, helping students see that environmental issues are not distributed randomly but are deeply connected to broader social issues. It also shows that communities are not powerless, but have agency - they resist, organise and create change.