Learning objectives:

- Describe the global waste flows of the fashion system and their impacts on people and nature

- Examine how labour, environmental harm, and disposal are made invisible in the fashion system and contribute to inequalities

- Understand the importance of labour rights to promote biodiversity and well-being

The worldviews, goals, values and rules that govern the fashion system are embedded in its practices.

Powerful fashion retailers present products as cheap and disposable by masking the human and ecological costs of fashion, especially when borne by communities in the Global South.

The final resting place of discarded clothes

Fashion’s waste problems are global and deeply unjust. Every second, the equivalent of a garbage truck of textiles is either burned or sent to landfill (UNEP, 2018).

And yet, many consumers in the Global North remain unaware of what happens to their unwanted clothing once it’s out of their homes.

Activity: Fashion waste - out of sight, out of mind (15’-18’)

Prompt: Watch the 13-minute video below: The final resting place of your cast-off clothing.

While watching, take notes to answer:

- Why are so many clothes discarded in Western countries, according to the women in the video?

- Why do you think so many clothes in Western countries are discarded?

- Why do you think discarded clothes end up in far-away countries?

- Is there anything you think you should change in your own practices and habits after watching this video?

The fashion system is guilty of overproducing (making more products than what are consumed). The fashion industry also stimulates individuals to overconsume (buy more products than they need) (Arthur, 2024, p. 12).

In sum, the fashion system produces more than consumers buy, and consumers are encouraged to buy more than they need.

By overproducing, the fashion industry overflows markets with clothes. More offer than demand drives prices down, leading to big brands selling their products cheaply. This practice by big brands makes it difficult for smaller, sometimes more sustainable brands, to sell their products.

Because many garments are sold cheaply, consumers see them as disposable, made to be thrown away after a few uses. This perspective ignores the real value of clothing, embodying natural resources and the time, effort and skill of the people who made them.

When thrown away or donated to charity, clothes do not just vanish. Some are burnt, which results in carbon emissions and air pollution, contributing to climate change and affecting human health. Others are often moved ‘out of sight, out of mind’ from the Global North to the Global South. These countries tend to lack the infrastructure or the financial means to deal with all this textile waste (Arthur, 2024, p. 11).

Is where you live or come from one of the countries receiving high amounts of textile waste?

How is textile waste dealt with? Who is most impacted by this textile waste?

Ghana is one of the countries receiving very high amounts of discarded clothes (Johnson, 2023). Textile waste turns beaches, rivers, the sea and even once thriving communities into landfills (Johnson, 2023). It’s not just about landscapes becoming less beautiful as they crumble under the waste. Waste pollution destroys the ecosystems that people rely on for their livelihoods, and damages people’s health. For example, fishing communities in Accra, the capital of Ghana, rely on selling fish to make a living. Now, they can catch more clothes in their nets than fish (Johnson, 2023).

Clothes are not cheap. The human and ecological cost is hidden behind the label prices we see in the Global North and is being paid by local communities and workers in the Global South.

Invisibility in the global fashion system

Activity: How well do you know your clothes? (5’)

Source: Activity from Parker, 2023

Prompt: Pick an item that you are wearing and answer the questions below, without checking. Make a mental note every time you know the answer.

- What is the brand of the item?

- What fabric is the item made of?

- Where is this item made, off-the-top of your head?

- Who made this item?

People tend to know the answer to the first question, but this is less the case with the following questions.

Where would you look to find out the answer to the question ‘Where is this item made?’

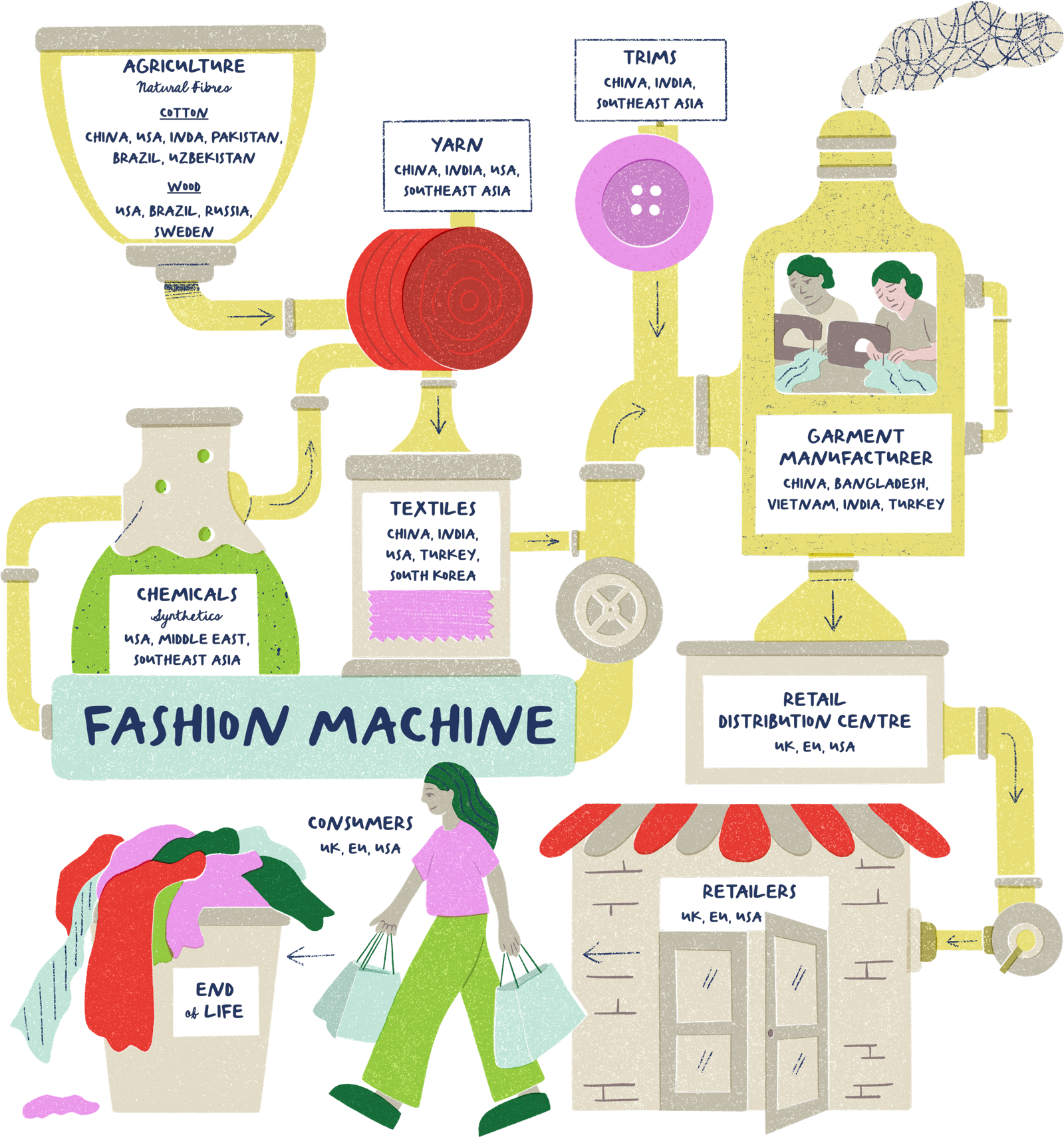

Look at the Figure 5 below representing the different stages in the lifecycle of clothes, and the countries where each stage takes place.

Which stage in the lifecycle of clothes does the ‘Made in X’ label corresponds to?

The ‘Made in X’ label only refers to the country where the item was assembled (the ‘Garment manufacturing’ stage above), but it hides the full picture. This label gives us no information about the other stages in the life cycle of clothes.

The European Union is trying to improve transparency around clothes by introducing the Digital Product Passport. The Digital Product Passport will provide a wide range of information on a product’s origin, materials used, its environmental impacts, as well as instructions for disposal.

Activity: What we don’t see, we don’t act on (7’)

Prompt: Watch the below video (2’) from Fashion Revolution presenting a social experiment where people are shown what is the hidden cost behind a €2 T-shirt, then reflect on the following questions:

- Do you think that people change their habits when they know about the hidden costs or the impact that their habits have on the world?

- What factors might prevent people from changing their habits even when they know the hidden costs?

- Consider: price, habits, convenience, social norms, personal and historical considerations

- Can you think of a time when you changed a habit after learning about an issue, and what led to this change?

- What do you think would make people improve their fashion consumption habits?

The global fashion system thrives on invisibility. Consumers are rarely shown the toxic rivers, exploited workers, or mountains of waste that make cheap fashion possible. As long as these realities remain hidden, the system can more easily continue with business as usual.

But knowledge alone is not enough. More and more people are aware of fashion’s problems, but many either do not have the means to change their habits, or do not feel like changing their habits would make a difference.

That is why transformation must point beyond individual awareness. It must challenge worldviews, goals, values and the rules of the entire system, to address the root causes of the problem. This includes what we pursue (growth versus wellbeing), whose lives and wellbeing we value, and who has power in shaping the future of fashion.

Unequal exchange

Have a look again at the countries and regions at each stage of manufacturing, distribution and disposal in Figure 5 above (section 4.2). Compare that with the countries and regions where clothes are typically consumed.

The fashion retailers in the Global North that we are most familiar with (the brands) rarely make the clothes that they sell. Instead, they subcontract companies in the Global South or in lower-income countries in the Global North to do that work.

This is because the costs of labour and extracting new natural resources are cheaper than in the Global North (Fletcher & Tham, 2019, p. 17) and because labour and environmental regulations in the Global South tend to be more relaxed or poorly enforced compared to those in the Global North.

This structure of work results in lower costs of production for Global North retailers, enabling Global North retailers to capture the bulk of the profits. In academic terms, this is called unequal exchange.

Unequal exchange refers to the unequal patterns of trade between the Global North and the Global South where Global North countries and companies use their geopolitical and commercial power to accumulate wealth through paying the Global South less than their labour and resources are worth (Hickel, et al., 2024).

By making the natural resources, the labour and the socio-ecological impacts in the Global South invisible, retailers make it possible for a €2 T-shirt to exist, and for that T-shirt to seem to ‘disappear’ after it’s thrown away.

But the costs of that T-shirt haven’t disappeared; they’ve simply been exported.

The importance of labour rights

Activity: The double standard in the fashion industry (5’)

Watch this video (2') by Fashion Revolution showing a group of 10-year-old children challenging the double standard in the Global North, when it comes to child labour in the fashion system.

Reflect on the following questions:

- Why is child labour accepted in the Global South but not in the Global North?

- Do you think there is anything that the fashion brands’ employees the children spoke to can do to trigger change?

- How can fashion workers feel more confident to advocate that their employer ensures children rights (and other environmental and human rights standards) are respected in their operations?

The fashion system thrives on inequality between the Global North and Global South, within countries themselves, and even among countries within the Global North.

The difficult work is pushed far away, where wages are lower and the working conditions are poor. Because of the inequality of the global trade system, people in Global South countries often have no other choice than to accept conditions which are contrary to children’s rights, and labour rights, and that most people would consider unacceptable in the Global North. This is the double standard that children denounce in the video. But human rights and justice should offer the same protections to all of us.

The collapse of the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh in 2013 killed 1134 people and several thousand more were injured, many with life-altering injuries. Families were devastated. This tragedy exposed the widespread exploitation and neglect within the fashion industry. Structural cracks in the Rana Plaza building had been identified the day before the collapse, but garment workers were still ordered to enter (Clean Clothes Campaign, n.d.). Profit was prioritised over workers’ lives. This horrific event became a catalyst for global calls for justice and safer working conditions in the fashion industry.

The fashion system cannot be transformed without securing and enforcing labour rights. Today, the industry is built on a model that extracts cheap labour, mostly from women and marginalised communities in the Global South, under conditions that are often unsafe, underpaid, and devoid of legal protections. These exploitative practices are not accidental - they are structurally embedded in a system designed to minimise production costs for maximum profit.

Labour rights, such as the right to a living wage, safe working conditions, freedom of association, collective bargaining, and protection from discrimination, are fundamental human rights. Ensuring these rights challenges the global fashion system’s dependence on unequal exchange, where the wellbeing of workers is sacrificed for the economic benefit of brands and consumers in wealthier regions of the world.

Protecting workers’ rights is also essential to promote biodiversity. When workers lack labour protections, they lack the voice or security to advocate for environmental protections in their workplaces, such as limiting chemical use, preventing river pollution, or demanding sustainable sourcing practices. Promoting labour rights and environmental rights are deeply connected: you cannot have one without the other.

Transformative change in fashion must therefore include legally binding labour standards, transparent supply chains, and accountability for corporate actors. A fashion system rooted in dignity and fairness for people is also one that is far more likely to support the flourishing of ecosystems, rather than their destruction.