Learning objectives:

- Explain what agroecology is, in your own words

- Evaluate the role of smallholder farms and agroecology in fostering biodiversity and food sovereignty

- Examine the impact of global agribusiness and agricultural subsidies on food system resilience and justice

- Reflect on the myth of scarcity and the false trade-off between feeding people and protecting nature

Who shapes the global food system?

The destruction of biodiversity through intensive agriculture is sustained by the goals of the dominant socio-economic system. Yield maximisation and economic growth are prioritised over care for biodiversity (Loučková, et al., 2025) and people’s wellbeing.

Large-scale industrial farms have been gradually replacing small-scale farms (or smallholder farms). Small-scale farms vary between less than 1 hectare to 10 hectares (Gladek, et al., 2017).

Within the European Union, the number of farms decreased by almost 40% between 2005 and 2020, with almost 90% of these lost farms being small-scale farms of under 5 hectares. Yet, the amount of land used for agriculture remained almost the same over the same period. This suggests the consolidation of land through large farms taking over small farms (Eurostat, 2022).

Globally speaking, smallholder farms play a vital role in feeding billions of people and tend to take a more sustainable approach to biodiversity. About a third of the global population relies on fishing, farming or pastoral activities for their food and income (Johns, et al., 2013). This is especially the case in the Global South, where smallholder farms are particularly important and most often exist as subsistence farms.

Yet, smallholder farms in the Global South have to compete against cheap, subsidised food imports produced through large-scale, intensive agriculture. This jeopardises smallholder farmers’ capacity to grow their own food and make a living, and puts their land at threat of land grabbing and speculation (Gutierrez Escobar, 2019).

Land grabbing happens when an individual or an entity (whether public or private) gains control of unusually large areas of land, for profit or resource extraction, in ways that harm local farmers, sustainable land use, food sovereignty, and human rights (Baker-Smith & Miklos Attila, 2016).

Speculation happens when ‘buying lands, good, etc., in expectation of a rise of price and of selling them at an advance’ (The Law Dictionary, n.d.).

Agricultural subsidies are financial incentives paid by governments to farmers to support food production. Watch the following video explaining the impact of subsidies on food production (5’) and reflect on the following question: Should governments subsidise large-scale monocultures, or smallholder diversified farms?

The global food system is characterised by a high concentration of power in the hands of a few transnational corporations, commonly referred to as ‘agribusiness’.

These few powerful businesses control every part of the global food system: from the sale of commercial seeds, pesticides, fertilisers, food trade, food processing and distribution and retail. These corporations exert undue influence on public policies, trade agreements, global multi-stakeholder processes, scientific research and popular discourse (IPES-Food, 2023) on food and food governance.

This concentration of power throughout the global food system has been identified as an important contributing factor to the current food system’s failings and resistance to change (Keenan, et al., 2023).

This prioritisation of economic growth and profit maximisation, and the concentration of power within the global food system are further reflected in the laws and policies that govern the food system. These prioritise the rights and interests of large agribusinesses over those of small-scale farmers and biodiversity protection.

In those areas where global political systems have less influence, such as those where ecosystems are managed by Indigenous People, biodiversity is often found to be the best preserved (IPBES, 2019). Yet, as is the case with the Cerrado biome, these areas are being increasingly encroached upon by agribusiness.

Do we have to choose between people’s access to food, and the environment?

There is overwhelming evidence that the global food system and its intensive production practices have been harming people and nature - from driving and keeping workers in poverty and poor health, to destroying biodiversity, contributing to climate change and degrading soil and water quality.

Yet, agribusiness tells us that we should produce even more food to address hunger, especially in the context of a growing global population and climate change increasingly affecting crops (A Growing Culture & ETC Group, et al., 2023).

The agribusiness’ way of telling this story makes people think that there is a choice to be made between feeding people by expanding the current food system, or downsizing it to reduce its environmental impacts, with the risk of not being able to provide food for everyone.

This is a false choice, and it is based on a false assumption. It is not the case that 783 million to 2.5 billion people around the world still face hunger or experience a form of malnutrition because we do not produce enough food. We already produce sufficient food to feed every human being. We produce so much food that there is enough to feed over 10 billion people (the highest estimation of population predicted for 2050) (A Growing Culture & ETC Group, et al., 2023).

Yet around 40% of all food produced globally is lost or wasted each year, from farms to households (WWF-UK, 2021).

Reducing food loss and waste across the food system is a simple way to reduce the food system’s impact on biodiversity, as it reduces production levels needed to achieve the same levels of consumption. Switching to predominantly plant-based diets would also reduce the pressure that livestock and related crop production put on biodiversity. Finally, other ways of providing food – such as food sovereignty (see below) - can help farmers, consumers and nature thrive in balance.

Is transforming the global food system even possible?

It is possible, at the same time, to provide everyone with nourishing and appropriate food, enable farmers and other food workers to live dignified lives, and protect and restore nature.

This would mean profoundly transforming the current industrial food system towards one that prioritises people’s wellbeing, biodiversity and low-carbon agricultural practices, over economic growth.

Watch this video (5’) explaining what agroecology is and how it works with biodiversity, rather than against it, to ensure people’s wellbeing within planetary boundaries. Based on the video, try to write down your own definition of agroecology, or elements that constitute agroecological practices.

Complete your notes with missing elements, if any, from the definition below, provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Agroecology ‘is a holistic and integrated approach that simultaneously applies ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of sustainable agriculture and food systems. It seeks to optimize the interactions between plants, animals, humans and the environment while also addressing the need for socially equitable food systems within which people can exercise choice over what they eat and how and where it is produced’ (FAOb, n.d.).

After watching the video and completing your notes, have a look at the inspiring stories and photos of communities around the world that put agroecology into practice, captured by the We Feed the World project.

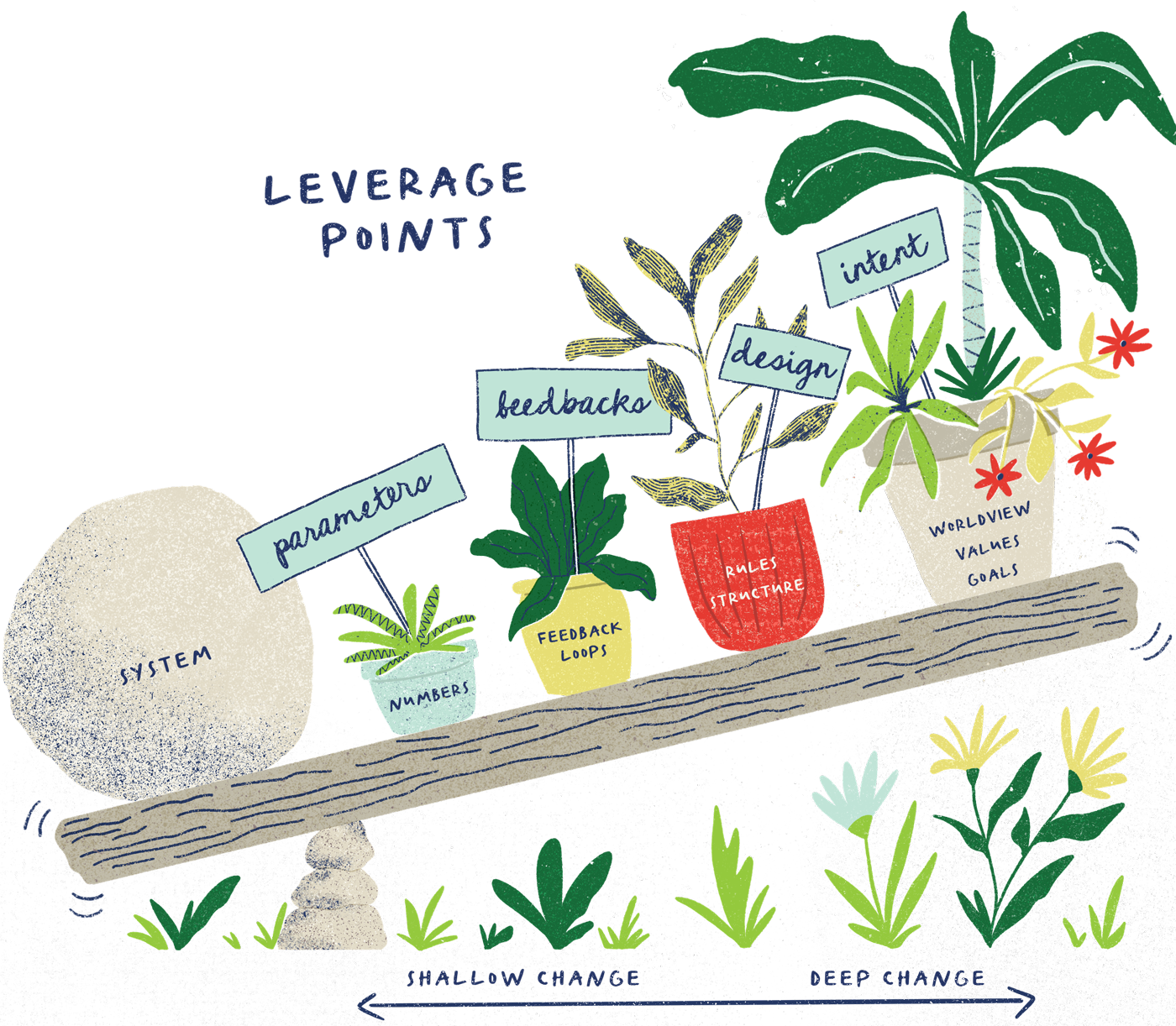

In its Diverse Values of Nature Assessment (IPBES, 2022), IPBES, the leading independent organisation that synthesises global scientific knowledge to inform policy on biodiversity, emphasised that halting biodiversity loss requires not just technical changes, but deep, structural transformations to how we live, govern, and value nature.

IPBES identifies four 'deep’ leverage points (2022):

- Redefining the good life

- Changing dominant values and behaviours

- Rewriting the rules of economic and political systems

- Centring justice and inclusion, especially Indigenous knowledge

These ideas align deeply with the principles of food sovereignty. Food sovereignty is more than a farming method - it’s a call to redesign our food systems so that they nourish both people and the planet, while shifting power from corporations to communities.