Planning Your Intervention

Thorough and effective planning creates the foundation for reliable data and meaningful outcomes. It ensures your nudging intervention is not just an isolated activity but part of a process that connects behaviour change with broader biodiversity goals.

In this video Ilkhom Soliev explains how to effectively plan a nudging intervention:

- Begin by clarifying your aims - what specific behaviour do you want to influence, and how does this link to biodiversity goals? Identifying the relevant biodiversity challenge will help you focus on the behaviours that matter most, whether these are choices about food, energy, waste or everyday consumption.

- Develop a research question or guiding focus – your research focus or question does not need to be highly technical, but it should be precise enough to shape the nudge you will test. For example, you may want to know whether highlighting health benefits of biodiversity, or showing its cultural value, makes people more likely to choose biodiversity-friendly options.

- Build relationships with partners – if your intervention requires a partner to host it - such as a retailer, workplace, school, or community space - you will need to identify and engage a willing organisation. Partners can provide access to participants, help implement the intervention, and in some cases scale out effective approaches. To encourage partners to support your project you might want to emphasise the mutual benefits: nudging experiments can provide them with new insights into customer or community behaviour, demonstrate their commitment to sustainability, and generate positive visibility.

- Secure permissions and address ethical considerations - clarify how the intervention will be carried out, what information participants will see, and how their responses will be used. Transparency is essential, but it works differently depending on the stage of the intervention. When participants simply encounter a nudge - such as information on a poster or trolley insert - they are free to ignore it, and their choices remain unrestricted. When data is actively collected - for example, through a follow-up survey - participants should be fully informed about the purpose of the study, how their responses will be used and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Prepare your materials - depending on your intervention, materials might include posters, shelf labels, trolley inserts, or digital displays that present biodiversity messages. Make sure your materials are clear, accessible, and visually engaging, and pilot them where possible to check they are understood as intended.

- Design and distribute your post-intervention survey - this survey could include questions on whether participants noticed and how they responded to the nudge, their attitudes towards biodiversity, and any changes in their behaviour. Ensure your survey will help you answer your research question and that the survey design fits well with your main research aim. Within the PLANET4B project, researchers conducted the survey verbally, recording participants’ responses. If resources are limited, participants can instead complete the survey independently. A copy of the PLANET4B survey script can be found HERE.

- Pilot the intervention– a small-scale trial helps to check whether the nudge works as intended and whether participants understand it clearly. Making adjustments at this stage can prevent confusion and wasted effort later. You can test the nudges with people outside your immediate team, such as friends and family, students, shoppers at a market, or visitors to the supermarket where the full experiment will take place. Ethical consent will need to be obtained for the pilot stage, as it involves direct participation from individuals. If resources allow, larger opinion polls can also be used. The aim is to spot and correct obvious errors and to gain an early indication that the approach is on the right track.

In this video Ilkhom Soliev explains best practice and accountability in designing a nudging method:

Carrying out Your Intervention

Once you have selected and designed your intervention, the next step is to implement it in your chosen setting. In the PLANET4B project, the experiment took place in a supermarket, where the aim was to test how nudges influence shopping behaviour.

1. Conducting the intervention

- If you conduct the study in one supermarket, plan for at least two days of data collection so that one day serves as the control and the other as the treatment. This is the minimum needed to compare results, though it carries the risk of producing too little data if customer numbers are low. Alternatively, you could run the study across several supermarkets on a single day, selecting a group of shops where half act as controls and the others as treatment sites. This approach allows comparison under the same conditions while increasing the overall sample size.

- In the PLANET4B project, data were collected on four occasions across two consecutive weeks, always on a Friday and a Saturday. The design alternated between control and intervention conditions in order to provide a balanced comparison.

- On the first Friday, data were collected under control conditions, with no nudging intervention in place (i.e. trolleys without inserts).

- On the first Saturday, the nudging intervention was applied, creating the intervention condition (i.e. trolleys with inserts)

- On the second Friday, the intervention condition was repeated, with the nudging measure in place (i.e. trolleys with inserts)

- On the second Saturday, data were collected again under control conditions, with no intervention (i.e. trolleys without inserts)

- This structure provided two control days and two intervention days, split evenly across Fridays and Saturdays. The approach ensured that baseline shopping behaviour (control group) could be compared directly with behaviour when nudging was applied (intervention group), while also accounting for potential differences between weekday and weekend shopping patterns.

- Aim to keep conditions as similar as possible to the control day - for example by running the test at the same time of day and on the same day of the week. This helps ensure that the only meaningful difference between the two groups is the intervention itself.

- Action the nudge, a nudge can be implemented in several ways, in the PLANET4B project the intervention involved putting posters in shopping trolley with information about biodiversity

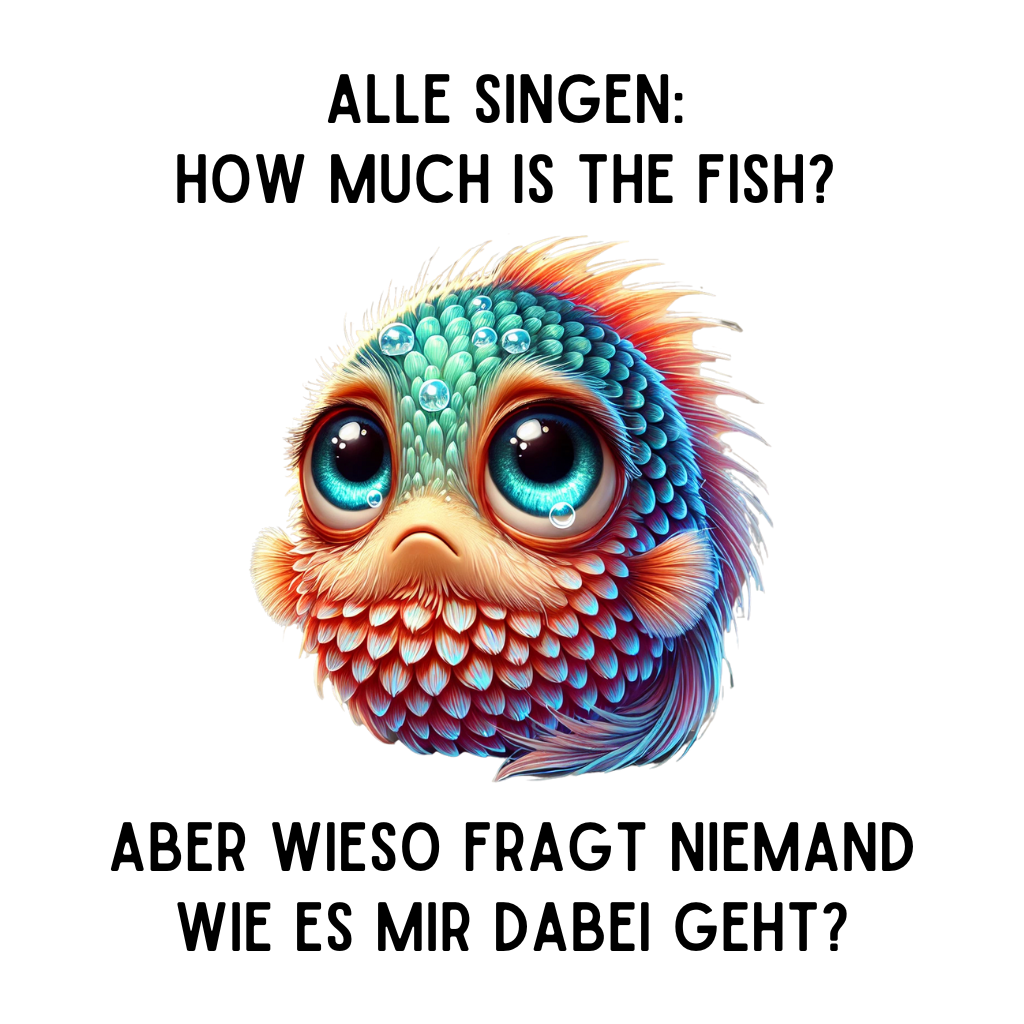

Below are some examples of the nudging signs that were inserted into the shopping trolleys during the PLANET4B case study:

Dr. Angela Merkel, former Federal Chancellor [of Germany]

Dr. Eckart von Hirschhausen

Prof. Dr. Harald Lesch

World Health Organization 2023

But why does no one ask how I feel about it *

*This poster was designed for a German audience as a playful nod to the popular song How Much is the Fish? by the German band Scooter, referencing its title to draw attention.

2. Engaging with nudging subjects

- Once the nudge has been introduced and participants have, or have not (i.e. control group), been exposed to it, you can approach them to gather data related to the specific behaviour of interest. In the PLANET4B project, this involved engaging with shoppers who had encountered nudges connected to their purchasing habits.

- After customers complete their shopping, approach them politely and invite them to take part in (e.g.) a short survey

- The survey should cover the information you have deemed relevant, as well as demographic information that would help you analyse the data

- To capture behavioural outcomes, ask for information about their purchases, such as a photograph of their receipt

- Conduct the survey as they leave the shop, when the shopping trip is still fresh in their minds – make sure you only approach adults unless consent has been explicitly secured for minors

Tips for collecting comparable data

- Aim to collect responses from a similar number of participants on both days

- Record any relevant contextual details (for example, unusual promotions, weather conditions, or store events) that might affect shopping behaviour

- Ensure data collection procedures are consistent across both days to strengthen the reliability of your results

- It is recommended to have at least 50 participants in both the treatment and control group

In this video Ilkhom Soliev explains the skills needed to design and manage a nudging project:

Analysing your Data

Once you have collected data from your intervention, the next step is to analyse it. Analysis allows you to understand whether your nudge had an effect, how participants responded, and what lessons can be drawn for future action. Depending on the type of nudging intervention, there may be specific forms of data analysis required.

In this video Ilkhom Soliev explains how data were analysed in the Supermarket Nudging Method:

Below are some practical tips to guide your approach:

1. Organise your data

- Bring together survey responses (or e.g. interview transcripts), receipts, and any observation notes in one place.

- Ensure data is anonymised where necessary to protect participant privacy.

- Keep a record of contextual factors that may have influenced outcomes, such as weather, promotions, or events.

2. Compare control and treatment groups

- Identify what happened when the nudge was not in place (control) and when it was implemented (treatment).

- Look at the main behaviour of interest. For example: did shoppers buy more of a biodiversity-friendly product when the nudge was present?

- Use simple statistical comparisons, if possible, such as comparing averages across the two groups – Regression Analysis is useful when your control groups are not directly comparable

3. Interpret survey responses

- Examine how participants described their reactions, intentions, or feelings about the intervention.

- Note patterns in demographic groups or types of shopper.

- Reflect on whether the nudge seemed clear, motivating, confusing, or irrelevant – it is possible a nudge can have negative side effects, so ensure these are documented too.

4. Look for patterns over time or across contexts

- If you collected data on different days, times, or locations, compare the results.

- Ask whether the effect of the nudge is consistent, or whether it varies according to context.

5. Connect back to your aims

- Revisit the original purpose of the intervention. Did the data suggest that the nudge worked as intended?

- Were there unintended effects, positive or negative?

- What lessons could inform future designs?

- What was not possible to answer with the data available?

- What questions are still outstanding?

In this video Ilkhom Soliev explains how nudging data can be used to understand behaviour and inform design choices:

Using Nudging Methods in a Researcher Context

For researchers exploring behaviour change through nudging, the method provides a real-world context to study how individuals respond to biodiversity cues in everyday decision-making. By embedding nudges into familiar settings, researchers can examine how social norms, emotions, and values influence behaviour without restricting choice. Observing and analysing these subtle shifts offers insight into how people engage with biodiversity in ordinary situations and what kinds of messages prompt reflection or change

Define research objectives

- Begin by clarifying what you aim to investigate through your nudging intervention.

- Objectives may include assessing whether particular nudges influence behaviour, identifying which emotional or cognitive cues are most effective, or examining how people interpret biodiversity messages within the routines of daily life

- Consider how situational factors such as spatial layout, time constraints, or social context shape responses to nudges, and whether any behavioural shifts are sustained beyond the immediate setting.

- Reflect on how your findings could inform practical strategies for designing biodiversity communication or policy interventions.

Data generation

- The method can produce a range of data types, depending on the design. These may include surveys, interview transcripts, photographs of receipts, sales records, observation notes, and contextual information such as promotions, weather, or store activity.

- Post-intervention surveys or short interviews offer valuable qualitative material, helping to uncover participants’ reasoning, feelings, or interpretations of the nudge.

- Quantitative data, such as the number or value of biodiversity-friendly products purchased, allow for comparison between control and treatment conditions.

- Managing this variety of material requires clear documentation and structured data storage. Keep logs of dates, times, and contextual notes, anonymise participant data, and maintain consistency across data collectors. Organised records support analytical reliability and ethical accountability.

Analytical strategies

- Analytical robustness depends on triangulating multiple forms of evidence and ensuring that findings are not based on single data sources or untested assumptions.

- Statistical comparison between control and treatment groups forms the core of the analysis. Descriptive statistics, cross-tabulations, and regression analysis can identify patterns in purchasing behaviour and test whether observed differences are significant. Attention should be given to confounding factors, such as store promotions or day of the week, which could distort results.

- Qualitative data offer complementary insights into meaning and motivation. Thematic analysis can be applied to survey responses or interview transcripts to identify recurring ideas, emotional reactions, or reasoning patterns.

- Observation notes can be coded to detect behavioural cues such as hesitation, reading of materials, or group discussion. Combining behavioural and discursive evidence allows interpretation of how the nudge was perceived and enacted.

- Triangulation across quantitative and qualitative datasets strengthens validity, creating a fuller understanding of the intervention’s effects. Comparative analysis across sites or time periods helps identify consistency or context dependence, while longitudinal follow-ups can explore whether awareness or habits persist.

Theoretical framing

- Nudging methods are rooted in behavioural economics, which challenges the assumption of fully rational decision making. They build on the work of Thaler and Sunstein, who argue that small changes in the presentation of choices, known as choice architecture, can steer people towards decisions that align with desired outcomes without restricting freedom of choice. Within this framing, behaviour is influenced by cognitive biases, heuristics, and social cues that shape how information is perceived and acted upon.

- Environmental psychology and social practice theory have reinterpreted nudging as more than a cognitive process. These perspectives view behaviour as shaped by habits, routines, and shared meanings embedded within social and material contexts. In this light, nudging becomes a situated intervention that works through cultural norms and everyday practices rather than simply correcting individual biases.

- Ethical and epistemological debates surrounding nudging question the assumptions it makes about autonomy, agency, and responsibility. Critics argue that nudging can risk paternalism, manipulate choice, or obscure the structural factors that limit behavioural change. Within sustainability research, it has been noted that nudging often individualises responsibility, though it may also be reframed as a participatory and relational approach that supports collective and reflective forms of behavioural design.

Ethics

- Ethical practice is central to field experiments involving human participants. Informed consent should cover all interactions that involve data collection, such as surveys, interviews, or photographs. Participants should be aware that they can decline to take part or withdraw at any stage.

- Since nudges operate subtly, transparency must be balanced with methodological integrity. Researchers should ensure that the intervention does not cause discomfort, manipulate emotions inappropriately, or mislead participants about the purpose of the activity.

- Data storage and reporting should follow institutional ethical guidelines, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality. When findings are shared publicly, consider inviting project partners or participants to review summaries or comment on interpretations, reinforcing trust and collaborative ownership of results.

- A reflexive and ethical use of nudging requires recognising that the method functions both as an intervention and as a research instrument, simultaneously observing behaviour and influencing choices. It is therefore important to remain attentive to how design choices, assumptions, and framings influence participants’ responses and interpretations. Ethical reflection extends beyond consent or transparency to include consideration of how nudging interventions affect people’s sense of agency and how they contribute to shaping societal understandings of biodiversity and value.

.svg)

.svg)