Traditional methods of recording biodiversity in Western science

Before the development of modern technologies such as DNA metabarcoding or satellite imaging, biodiversity in Western science was recorded through field observation and manual techniques. These approaches remain widely used and continue to provide the foundation for biodiversity monitoring.

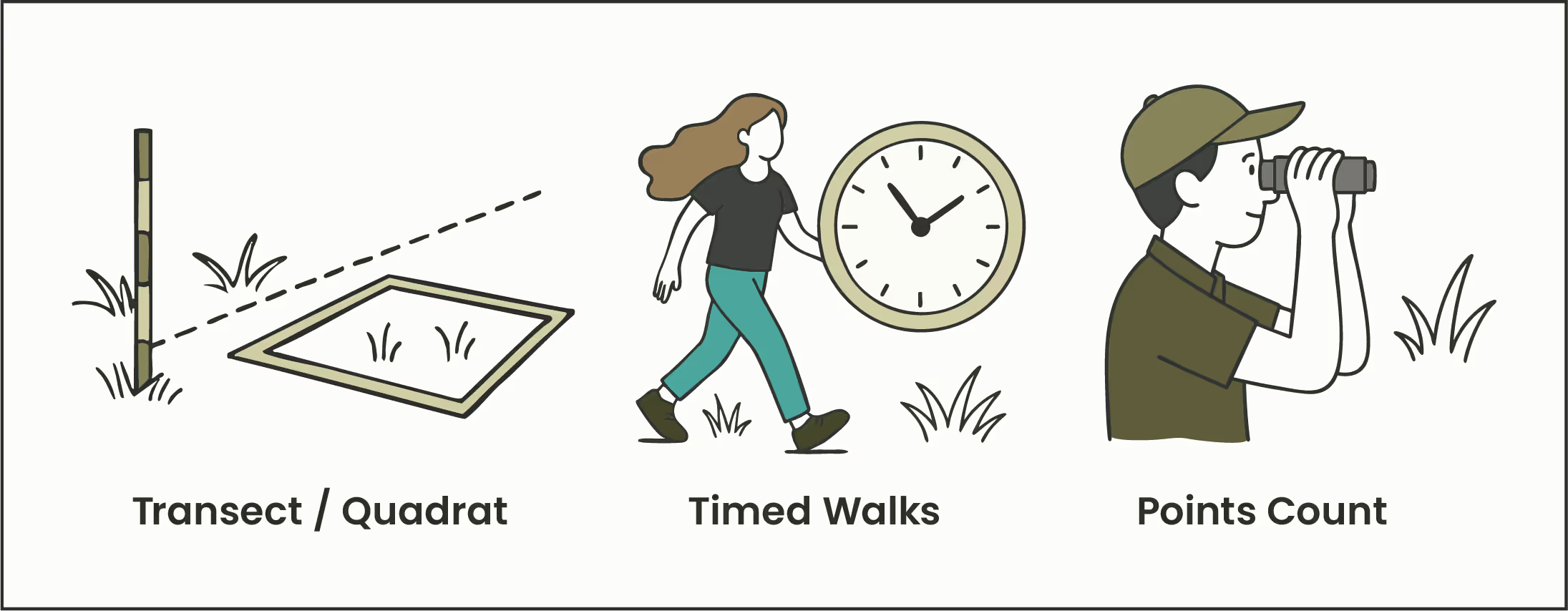

Field surveys and species inventories

Experts identify and record species within a defined area using methods such as transects, quadrats, timed walks or point counts. Although time-consuming and reliant on taxonomic expertise, they provide highly specific, species-level data.

Vegetation mapping

Plant composition is systematically recorded in plots or along gradients. This provides detailed community-level data and supports habitat classification. Botanists and entomologists may also collect specimens for identification and preservation. Such collections provide valuable reference material, although the method can be destructive and is not appropriate in sensitive habitats.

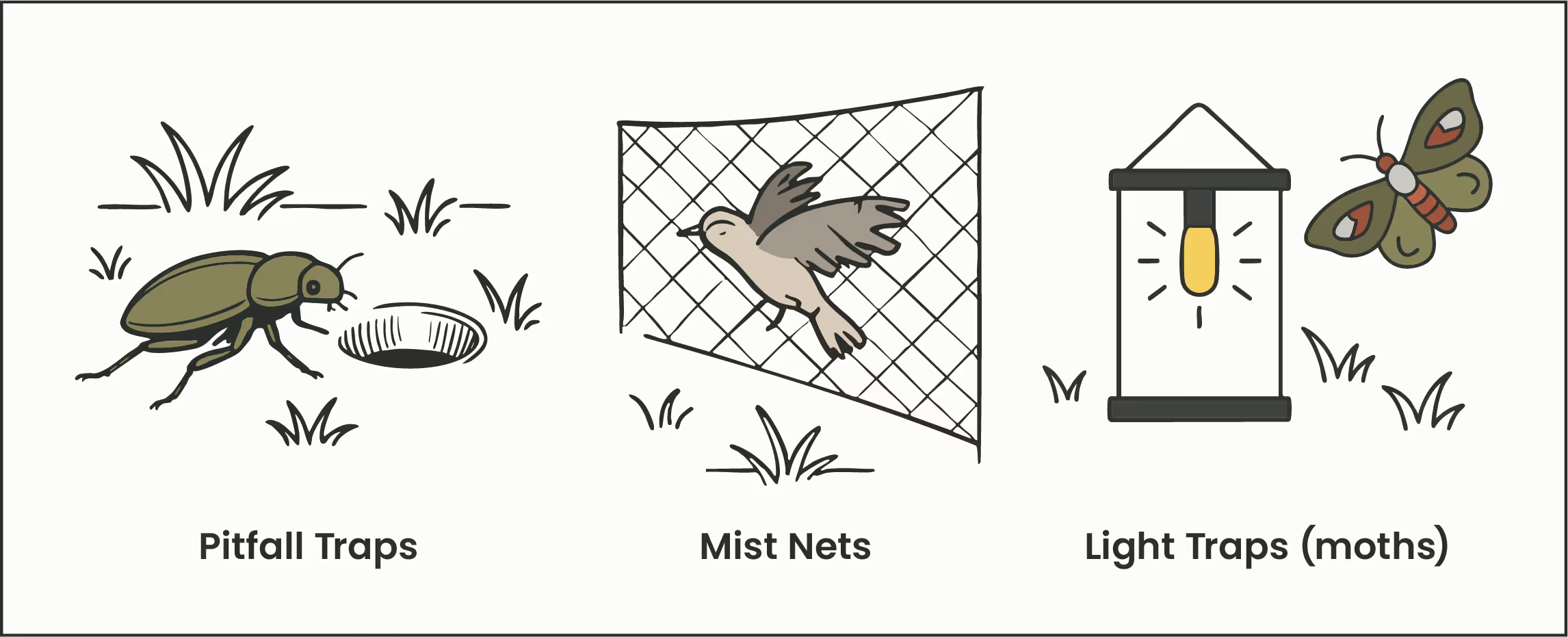

Trapping and netting

For more mobile or cryptic species, trapping and netting are used to monitor abundance or behaviour. Common methods include pitfall traps for ground insects, mist nets for birds and bats, and light traps for moths.

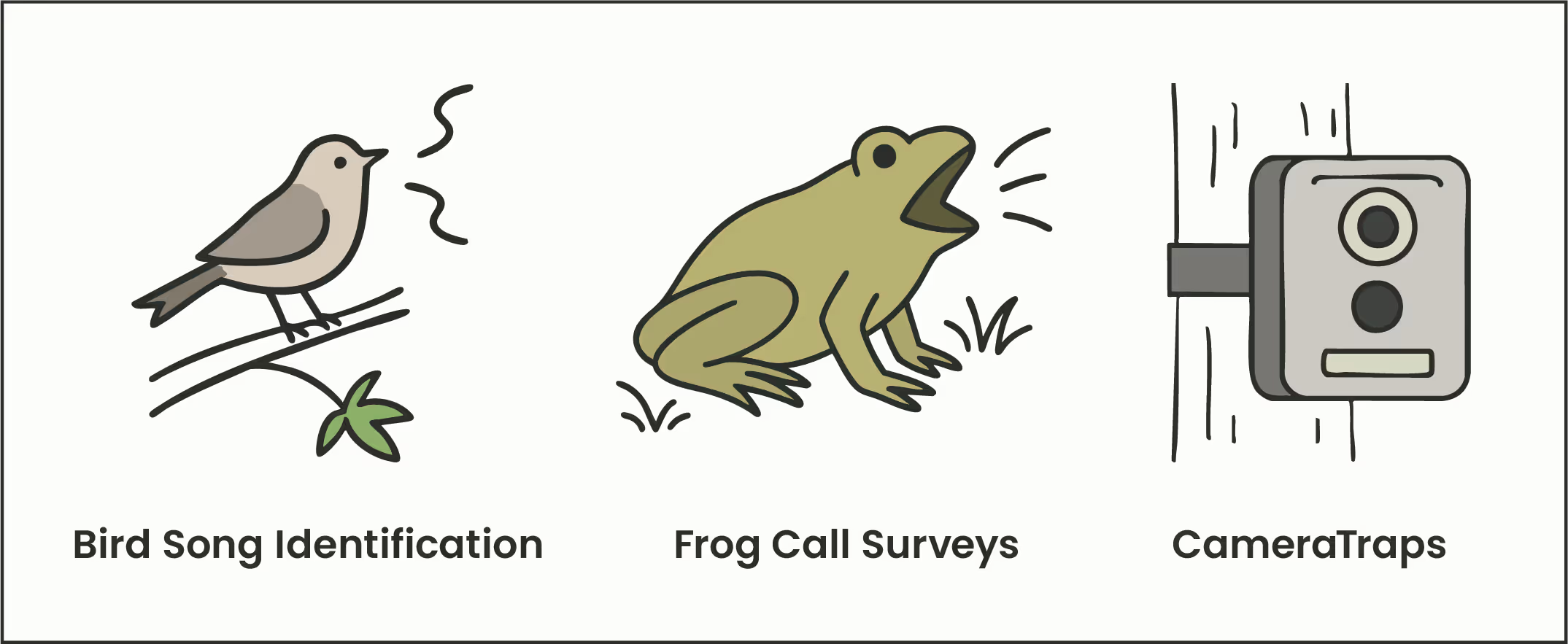

Acoustic and visual monitoring

Some species are monitored by sound or sight, for example bird surveys using song identification, frog call surveys, or the use of camera traps for mammals. These methods are non-invasive and effective for elusive or nocturnal species, although they require high field expertise and can be vulnerable to observer bias.

New and emerging technologies

Technological advances now provide new tools for biodiversity recording. Remote sensing using satellite or aerial imaging can monitor habitat loss and large-scale ecosystem change. Environmental DNA (eDNA) detects species from traces left in soil, water, or air, producing detailed presence–absence data. Advanced acoustic recording is increasingly used in habitats such as forests and oceans. These approaches depend on strong baseline data, and expert interpretation. As with many research tools, it is important to be mindful of power dynamics and equity concerns, including who controls the data, who has the skills to interpret it, and whose knowledge is recognised or excluded in the process.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

Alongside these scientific approaches, growing recognition is given to Indigenous and local knowledge of species and ecosystems, often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge. TEK provides long-term, place-based insights and may highlight species or behaviours absent from scientific monitoring. Integrating TEK with scientific methods is still developing, but it offers vital perspectives on biodiversity and ecosystem change. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass offers a rich reflection on these knowledge traditions.

Biodiversity Metrics

Community and Population Metrics

Once data are collected, they need to be presented in ways that reveal patterns. A common approach is to measure abundance or biomass, meaning the number or weight of individuals in a population or community. These data can then be used to calculate measures such as beta diversity (comparing biodiversity between habitats or ecosystems) or turnover rates (how species composition shifts over time or across locations).

Biodiversity indices and databases

Composite indices are widely used to track biodiversity trends and to inform policy, from setting targets to monitoring progress and communicating findings. Examples include:

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

A global indicator of biodiversity health that categorises species from Least Concern to Extinct. It provides information on distribution, population size, ecology, threats, and conservation needs, and is used to guide policy and conservation action. - Living Planet Index

Adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity as a global indicator, this index tracks vertebrate populations worldwide and is maintained by WWF and the Zoological Society of London. - Biodiversity Intactness Index

Developed by the Natural History Museum, London, it estimates how much of a region’s original biodiversity remains - datasets are freely available.

Biodiversity is also monitored through species groups recognised as ecosystem indicators. For example, the EU Nature Restoration Law highlights the Grassland Butterfly Index and wild bird indicators Additional indicators can be found through GEO BON.

Finally, detailed records of individual species are accessible via the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) which collates biodiversity data from around the world.