Response-ability

In addition to considering further Tronto’s fifth component of caring with, another concept which it is also timely to introduce at this point is: ‘response-ability’. Deriving from the scholarship of Donna Haraway and Vinciance Despret, the incorporation of this concept arguably adds further analytical power to Tronto’s care framework.

In simple terms, just as caring with is approached in this MOOC as comprising (more than) the sum of the preceding four phases of care practice (about, for, giving and receiving), so too can response-ability be understood as the culmination of the accompanying ethical elements (attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, reciprocity), and both the basis for, and outcome of, caring with.

Through their respective works, Haraway and Despret each offer up response-ability in the context of understanding the becoming ‘with-ness’ of more-than-human relations and how to enable multispecies flourishing – an extremely rich vein of complimentary scholarship, which we return to in greater detail in Lesson 5 of this Unit.

In accordance with FCE theory more broadly, response-ability is, thus, not to be understood as a fixed state, but rather a quality in a constant state of becoming. As Haraway notes: “new openings will appear because of changes in practice and the open is about response” (2008: 90). This openness is evocatively depicted by Despret (2013) in her offering of a queer more-than-human illustration of becoming response-able as follows:

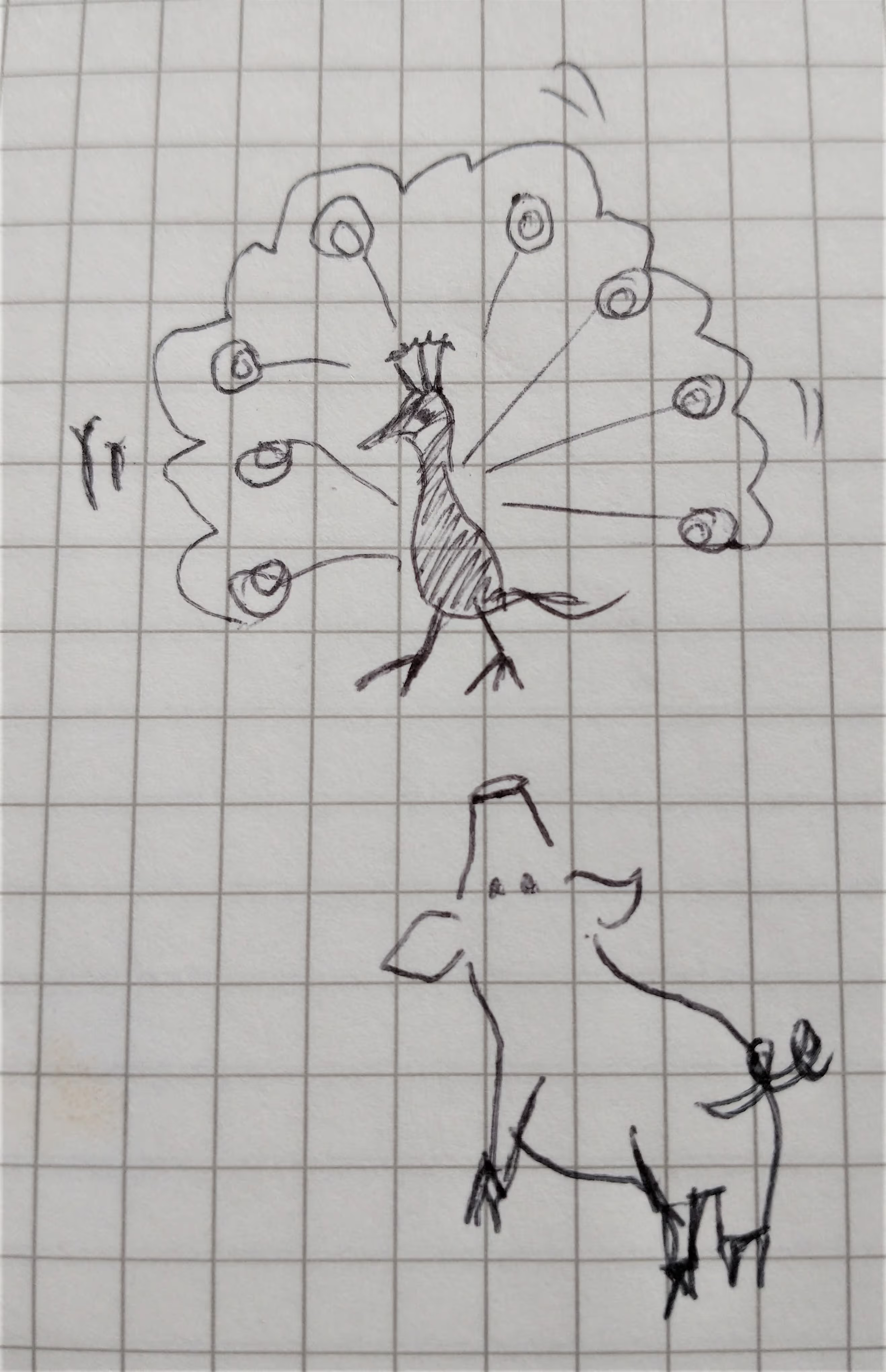

If the gaze of a pig may matter for an exhibitionist peacock, why shouldn’t one take into account […] the fact that the pig, a notoriously curious and sensitive being, might have responded to the former, looked back at it, and might have been affected in such a way that affects the peacock in return? Why not imagine these two beings liberated from pure reproductive motives, and enjoying together an unprecedented, creative, improvised, and queer “becoming together”? (Despret 2013:33)

Aligning one’s response-ability for caring with another, be they human of otherwise, occurs through practice and over time. In order for a relationship of response-ability to flourish, it is dependent upon what Haraway (2008), drawing on Despret (2004), eloquently refers to as care givers and care receivers “becoming availableto each other, becoming attuned to each other, in such a way that both parties become more interesting to each other” (Haraway 2008: 207 [emphasis added]). It is through this same process of attunement that they also become “transformed by the availability of the other” (Despret 2004: 125).

Also directly relevant here, when it comes to enabling response-able practice, is the attention Tronto affords to ‘ability’ factors. She notes how “good care will require a variety of resources [abilities] material goods, time and skills” (1993:110). Moreover, with these resources often in short supply, one of the realities of practicing care can be the need to make judgement calls on how best to distribute them, especially where the care needs are multiple (Law 2010).

Due to the relational nature of care practice, the degree and range of response-ability achieved will continue to evolve with each new case and context encountered. The skills of a care giver, however advanced, will not necessarily match the needs of every care-receiver within their field of practice. They may very well also be shaped by the extent to which the values of two or more individuals align with regards to what types of care needs should be prioritised in any particular setting – something which we will dwell upon further in Unit 3 in the context of the different scholarly realms of research, teaching, doctoral supervision and net-weaving.